COMMENTS ON OUR GARDEN

Whoever goes for a walk in the natural garden of Café Botanico with an attentive eye will come across unexpected objects: Little black labels with white writing on them dangling from branches and twigs decorating beds and fences – at first sight they have nothing to do with the flora of natural gardening. They neither read names nor do they give any explanations concerning the plants. They are just cryptic notes.

One of the labels reads: For how long must a species of plants live in a testing field in order to feel at home? Another one asks Where is the borderline between “domestic” and “exotic”? Among shrubs and herbs the little black labels are initiating a discussion we are being confronted with more and more often these days.

A debate over who is allowed to settle and thrive within the boundaries of a garden: Only indigenous plants are allowed to live here, but they may only do so, if they neither behave too dominantly nor show any signs of weakness. Didn’t we have that before?

It doesn’t just seem to be the kind of debate of an Internet forum transferred into the Neukölln garden scenery – it is one! To be exact it is an online debate about origins and spread of plants with political connotations and sometimes cheap comparisons. Berlin artist Roland Schefferski has planted the anonymously posted contributions from the virtual world into the real world, i.e. into the environment close to nature behind Café Botanico.

Schefferski’s“Comments on our garden” – on display since 27th Sept 2015 – are an artistic intervention using the green microcosm as a metaphor, i.e. as a symbol of a marked off area for a supposedly closed society still discussing the old order, unaware of the revolutionary influences from outside that can’t no way be evaded.

The way a garden is laid out is very telling about the person designing it. Are the beds arranged neatly and the hedges cut back? Are new exotic plants – even weeds – allowed to grow on his soil? The metaphor of the garden serves the artist Schefferski as a means to point out discrimination of strange ways of life and their exclusion from everyday life.

Roland Schefferski grew up in Poland. He emigrated to West Berlin in the early 1980s. He first carried out his work in a restored farmer’s garden in Brandenburg. That was in 2008 – long before the big wave of refugees that will completely alter our society. The question is: Which way are we going to lay out our metaphorical “society garden”? Will we fence it in or will we open it for new “immigrated” and exotic species? This question must be asked in a completely new way. But even the people discussing the issue in the Internet forum at that time realized: A totalitarian garden? - A horrifying idea!

Christoph Rasch

This excerpt is a fragment of a presentation for the Comments on Our Garden Project at the Nature Garden C. Botanico in Berlin, 2015

IN MEMORIAM

In his photographic work In Memoriam Roland Schefferski responds to the history and the specific function of the Glasshouse[1] as a waiting room attached to the neighbouring funeral parlor. The image shows a fragment of an empty bed, traces of the human body imprinted into the sheets. Questions arise about the identity of the absent person: what happened to this person? Where is the body now? The perspective of the photo is reminiscent of Andrea Mantegna’s famous foreshortened painting Lamentation of Christ (1490-1500,) where the body of Christ is shown from the feet forward. Schefferski documents the traces, which his body leaves after getting up from hotel beds in different cities like Paris, Regensburg or St. Petersburg. While in Mantegna’s painting the main focus is on the human body, Schefferski on the contrary is preoccupied with its absence.

In the site-specific installation Unity and Duality, Schefferski combines elements of his older works from the series of Drawings in Snow and Drawings in Sand, which are arranged resting on piles of art magazines, newspapers and catalogues. The pillars of various publications are vast data banks, which have been important during Schefferski’s artistic career. The images of the drawings series are framed yet they are no longer hung; they have been taken down. Supported by the pillars of magazines and books in English, Polish, Russian and German, the frames face upwards to the viewer. It seems as though the represent a greater spectrum of images. How does the artist form compositions that deal with history? What is the outcome of decisions made to exclude or include information? The emptiness outlined in the sand suggests the inevitable omissions made whilst recording and presenting histories.

1 The Glasshouse was a transitional space, built at the turn of the century, positioned between a small chapel and a funeral parlor (today Café Strauss) at the Friedrichswerdschen Graveyard in Kreuzberg, Berlin. The building is one of the few remaining buildings from this period following WWII. These pieces have been specifically created for the Glasshouse; they respond to the Art Nouveau interior of the space and its particular history.

Elena Gavrisch

This excerpt is a fragment of a presentation for the Two Hints in One Project at the Glasshouse - Culture Chappell in Berlin, 2013

FROM THE LIFE OF EUROPEANS

In 2011 the Lubusz State Museum (Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej- MZL) asked Roland Schefferski to use in his artistic work a bundle of one thousand and two hundred glass slides from the Jewish Museum Berlin disbanded by the Nazis in 1938. This set of glass slides was originally part of a larger collection of three thousand, which were available to public for education and research in the Jewish Museum founded in 1933 in the Oranienburger Straße in Berlin. These slides measuring 98 x 84 mm show portraits, artworks, buildings, views of the city, books and original Jewish ritual objects, archeological sites in the Orient, as well as scenes from the Jewish everyday live in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some of those photographs were brought to the Lubusz State Museum though Lower Silesia as a set of approx. one thousand and two hundreds glass slides after the end of the World War II.1

For the first part of his project bearing the title From The Life of the Europeans, Schefferski developed a communication strategy. He commissioned a large edition of copies to be printed from chosen images of the glass slides including some information about their origin. In December 2011 those printed copies were spread among the libraries in towns near German-Polish boarder in Frankfurt (Oder), Guben, Słubice, Szczecin, Zielona Góra and Zittau. The copies were inserted by the library staff into the books and newspapers borrowed by the public. In this way he communicated to the library users though a subtle action, which did not require their response. This intervention continued until all copies of the edition were disseminated.

Roland Schefferski reacted (...) in the second part of his project under the same title From The Life of the Europeans. His response was an installation divided in two spaces, at the Lubusz State Museum in 2012. In the first room he installed transparent glass shelving going all around the room just below the ceiling, on which he spread a thousand and two hundreds empty glass slides, cut in the same shape and size as the original slides given to him by the Museum. The empty slides referred to the absence of images on the subject in the cultural memory. In the other room, however, those “missing” images were projected on the wall in sequence. The wall text in the exhibition revealed information about the original slide collection from the destroyed Jewish Museum in Berlin, but the images of the actual inventory were not shown. In this way the artist intended to divide spaces into one preliminary empty room allowing the visitor to reflect and experience a space full of symbolic meaning and a second space purely dedicated to informing public about the original images.

1 The collection of slides from Zielona Góra was the subject of the Symposium at the Center Judaicum in Berlin. The accompaning conference volume was published by Jakob Hübner: Slides Collection of the Jewish Museum 1933-1938 in the Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej. Collected Pictures – Lost Worlds. Workshop in the Centrum Judaicum on the 6th and 7th December 2007 (Against suppression and forgetting, 7), Berlin 2009.- 2011 the slides were shown in the exhibition ‘In search of a Lost Collection. The Berlin Jewish Museum 1933-1945’ in the Centrum Judaicum.

Axel Feuss

This excerpt is from the essay “The Missing Picture” originally published in: Recall - catalogue by the Lubusz Land Museum in Zielona Góra, Poland 2014

reCONSTRUCTION

In his exhibition exposé Roland Schefferski uses a quote by Wolfgang Pehrt, which I will not deny you: “Well, history has always maintained a relationship to history, otherwise it would not be history. To relate to the past by way of recalling and thus to step away from the idle flow of occurrences, well, that is what makes historicity.”

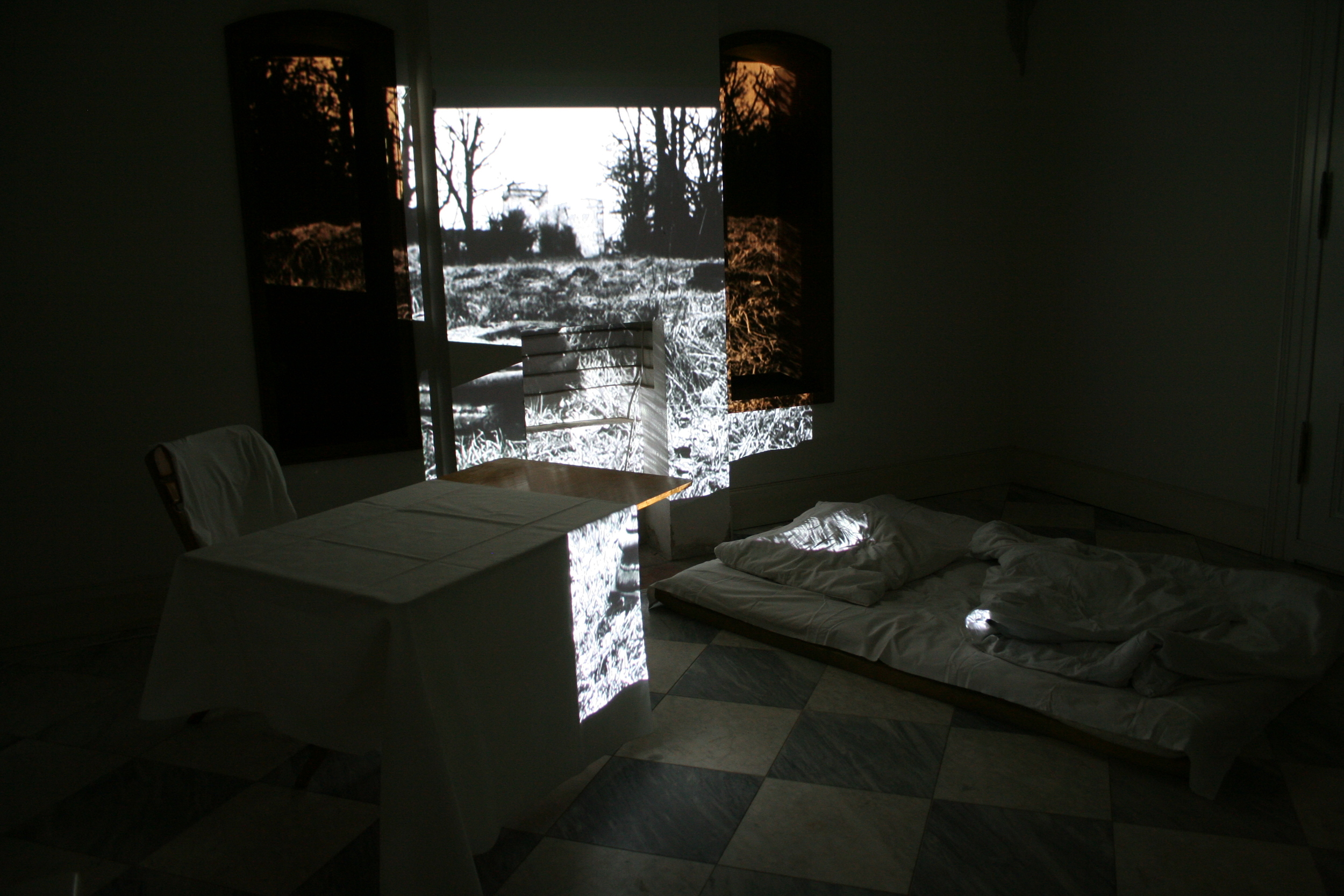

The quotation is taken from the book “Schinkel and beyond Schinkel. Attachment and freedom when dealing with history.” It seems like a hand fitted philosophy of the work that the artist has created for the Temple of Pomona, a building constructed by Friedrich Schinkel at the age of twenty. At first glance the temple itself appears untouched. One has to look closely. A few details, initially inconspicuous, become apparent with time and irritate the visitors, seduce them almost to explore the indoors further. But they are hardly in your face. The name tag, the door bell, the peep hole are only noticed at second glance. Shielding the face from daylight one can get a glimpse of the indoors room, which seems to be lived in. Black and white projections of historical photographs from the year 1965 appear on the walls, niches and the unfinished fireplace. The images are taken during a time when the temple was still in ruins. A lucid triptych, which yields to another, appears on the north-facing wall. The Cella is bathed in various different light moods that make the eyes wander and the inner self aware. Ascetic fixtures and fittings emerge. A piece of clothing on a chair, a table with a half fitted table cloth that becomes partial projection screen for a few moments, a bed that seems used.

Roland Schefferski feigns his presence and thus eradicates the boundaries between public and private space at the Temple of Pomona, which could also function as a studio space. Evidence, however, indicates more than just a temporary appropriation of the Cella. The act of privatisation implicates the fact, that the artist has become himself a part of the room that he arranged. Indeed, he even remains part of the physical space that is accessible by the audience, as his physical presence has been installed there and the process of arranging a room is a continuing one.

Why does Roland Schefferski title his work “reConstruction”? Within such a historical building that calls for public recollection, even this very activity is privatised when personal memories arise. Born in Poland, the artist studied at the academy in Wroclaw and has been living in Westberlin since 1984. The West-Polish roots of his family play just as important a role, as his admiration of Schinkel's classicism, which may have been stirred in the city of Thorn where his grandfather lived. Schinkel had built a church there, which is used as a cinema today. The exact origin of his admiration, however, is unknown. His childhood memories are most accurately presented though within the brass door sign that he collected from a Berlin engraver in order to mount on the door of the Temple of Pomona, and that resembles in all detail the sign that his grandfather, who bore the same surname Schefferski, had on his door.

Returning to our philosophical starting point, the term reconstruction denotes both the result and the process. Reconstruction in terms of result would be the building itself, which was reconstructed and made publicly accessible in 1993. A constructive act that was not completed on the inside, mainly due to the lack of written records. The Cella remains a fragment and thus draws much more interest from artists such as Roland Schefferski than the Corpus.

Upon ensuing inquiry, Schefferski replies: “My reConstruction is an artistic act which corresponds to Schinkel's conception. In his architectural textbook we can read the following statement: History has never copied earlier history, and when it did that, such an act never accounted towards history, as history somehow comes to a halt within such an act. Only such is a historical act which in some manner introduces an excess, a new element to the world of which a new story and history can be formed and continued.”

In his Berlin poem “balsam” the contemporary Catalan author Narcís Comadira ironically depicts “Schinkel's eagerness to build a new Athens” in conjunction with the state of the buildings today.

Quote

„I stroll along broad arcades,

examine the patched up spots of the pillars.

The spirit of people and buildings

make plastic surgery vanish in thin air.”

Do pay attention to the sensitive interventions of Roland Schefferski who has not presented us with a cosmetic act, but established a comprehensible connection to the architecture and cultural history of the Temple of Pomona, which we can perceive by the act of viewing.

Thomas Kumlehn

This excerpt is a fragment of a presentation for the reConstruction Project at the Temple of Pomona in Potsdam, 2009

“The reConstruction piece is quite interesting as it deals with perception and erasure as equal processes. They relate to the manner in which experience enters into and becomes memory. This would seem close to how we recognize art through form as being dependent on the experiential in order to exist. Language in this case would appear secondary as it begins to function in the past tense as being withdrawn through the a posteriori dimension that codifies the placement of art within our experience.”

Robert C. Morgan

A MODERN PRAYER

For some time now, EL Gallery has been accustoming viewers to exhibitions that explore the links between the pieces and the interior, eliciting artists’ responses to this remarkable exhibition space. Artists expressing themselves in Elbląg are expected to tie their work to what they find here, to acknowledge the context of the former church in their work. I would like to express my conviction that the unusual interior of EL Gallery, miles from the model of the white cube – that is, from the majority of the world’s exhibition venues – should, or even has to stand out with the exhibitions it houses, which upset viewer expectations, knock them off balance, making them interrogate themselves and others about the status of this place, the pieces on display, and an even more rudimentary question: What is art? The gallery’s placement in the old church makes sense if we do not pretend that this is a gallery like any other, that the building’s architecture makes no difference. Because the form of the architecture is significant, the demands of the art within are greater.

EL Gallery, to my mind, is a place where artists are forced to negotiate meaning – of what they brought with them and of what they find there. This is why reviving this special place requires engaging all its potential – its drawbacks and advantages. To this way of thinking, it is also a place for taking risks.

Roland Schefferski scattered the floor of the galley with daily newspapers from Berlin and New York, the home cities of the artists making the exhibition. In the crumpled papers, the artist placed mp3 devices playing recordings of a conversation he had with Monika Weiss about art, or relations between artists. At the same time, Schefferski alluded to the history of the building – he placed pews in the side nave, specially borrowed for the occasion from an Elbląg church, and called attention to the interiors “through smell,” with incense used in Catholic masses.

Schefferski’s question addressed the interior’s memory of itself, and how we remember and identify the architectural form with its function. Can we revise our memory by recalling smells, the murmur of conversations, by setting up pews? EL Gallery, once a temple, became a temple of “absence” or “lack” for the month of the exhibition. A place which Schefferski – now an atheist, though raised in a religious Catholic family – always has at the back of his mind. TheConversation / Beginning exhibition is an important one for him personally, as well. The concept, in which the artist travels into the past, is evoked in a somewhat nostalgic fashion through memories of details, like smells or whispered prayers.

For Schefferski, the central question was finding a descriptive category to bind his philosophy of life and his relationship to the interior of the onetime church. He found this category through formulating his vision of the absence and abandonment of the place.

The category of absence is conceived as simply the absence, or death of God. A world in which God is absent and man is condemned forever give meaning to all of existence, which we might reasonably call a tragic world. The essence of this tragedy is the affirmation of life. In showing the ruins of the world, the old, abandoned church, with its traces of onetime presence, Schefferski shows the absence of God, the emptiness of this place.

The only source of meaning is (or can be) man. God must die not so that man could be resurrected, but so that existence did not end up utterly absurd. At the same time, the absence of God is, I believe, a premonition of nothingness, the void, which can only be opposed by heroic freedom and the creation of value. Schefferski finds this value in a relationship with another person – in a CONVERSATION.

There was a third person in this conversation – the interior of the former church, with which the artist interacted. Conversation is always a linguistic act. How then, to involve a silent, empty, and vacant space? There are two options – either come to terms with it, listening to its special rhythm, or the opposite, disrupt it, and end up showing primarily your own ego.

It scarcely needs proving that every understanding, artistic or otherwise, is generated through language. When we try to listen to the space of the old church and exhibition we come across odd idioms: an “unspoken agreement” or “tacit consent.” We have all been witnesses to events that have left us speechless. All these categories are, in my opinion, more manifestations of language, emanations of understanding and having understood.

Something that leaves us speechless is also a kind of speech, and one that is less the end than the beginning of a statement and… a CONVERSATION.

The experience of a conversation, as well as the experience of Understanding, presuppose the existence of difficulties, of obstacles in reaching an agreement. The fact that something is foreign to us, provokes us, or disorients us, also initiates the process of Understanding. If, then, we want to make the understanding process central to our existence, we must remove this phenomenon from the process that precedes it – from discord or conflict. The ancient Greeks had a beautiful expression for this state – atopon. This word was used for a situation where understanding was impeded, through astonishment, surprise, a reaction to something unexpected.

At EL Gallery it has been a long time since we saw an exhibition that disrupted the place, its character, and drew out the nature of its abandonment, its vacancy.

In this way the artists call attention to the place itself in a delicate and subtle fashion, to the memory of the place, but also to us – familiar with this place and its unique value and character. The artists wanted to change how we perceive the place, to change our experience of it. They wanted to provoke the viewers to change their rhythm of taking in an exhibition, listening to the subtle murmurs, sounds, and smells that reach them. To give sentiment freedom to roam. Pews, the font, and the smell of incense accompany memory – our organ for being in the world. Through the memory of experience we cull everything from the past that influences us in the here and now.

Jarosław Denisiuk

The above text is excerpted from the article "Miejsce Ryzyka" published in: Tygiel - Kwartalnik Elbląski nr 3/4, Elbląg, Poland 2009

GOOD COIN

Many inhabitants of the border town of Słubice, and Frankfurt, its counterpart located on the opposite bank of the Odder river, were lucky enough to find in the street an intriguing coin, a material mark of the action by Roland Schefferski under the Słubfurt City project.

Monetary intervention has been yet another unconventional action by the Berlin artist, pertaining directly to the complex Polish – German relations. He has referred in his art to this issue a number of times, as a spokesman for an international dialogue. The history, memory, accounting for the past, as well as the contemporary ramifications of being neighbours have been the topic of his artistic deliberations.

The art by Schefferski has been based on an intellectual reflection expressed by means of performances exceeding traditional ways of representation. He has been involved with everyday life, frequently situating his works in a public space. A street, a store have been for him the places as good to present art, as a gallery or museum. The diversified tools and media he applies serve merely to visualize an intended concept. Initiating the Słubfurt City project, he decided to make for this ccasion a coin, especially for the inhabitants of Słubice and Frankfurt-on-Odder. Working on it, he has taken into consideration various aspects of money functions, stressing its role as a social phenomenon. He has referred to the concept of common European currency. A huge operation of introducing Euro in the European Union countries at the beginning of 2002 was supposed to be a guaranty of the continental unity and the united Europe’s dream coming true. Today, this issue seems to be more complex, though global unification is inevitable. For the time being, if Poland wishes to enter the “Euro zone”, it has to meet strictly defined convergence criteria in the coming years. The artist got ahead of this process making a coin earmarked for Poles and Germans living on the opposite banks of the Odder River bordering two states. In the past, Słubice and Frankfurt were one. The state mint in Warsaw produced Schefferski’s coin. At the first glance, its appearance, shape and the material it has been made from, resemble the one Euro coin. The artist has circulated his coin in quite an unconventional manner. He has “lost” several hundreds of them in various locations of both cities, being certain that they will be found. The action has been registered with a movie camera. The finders’ reactions have been emotional, as though they were finding real coins. Thus, the responses have been diversified; from joy through anger, as manifested by one Frankfurt inhabitant who simply threw it in a dustbin. Certainly, the informational function of the coin has been more significant. It has made one think. This has been a kind of a “correspondence” that the author of the monetary intervention wished to pass to a receiver. The coin obverse displays the 1 digit and the explicit inscription in both languages: Das betrifft dich – To dotyczy ciebie (That concerns You). Addressing this message to a single person, he draws one’s attention to the common – resulting from the past – responsibility which also applies to the present and the future. The artist, however, is afraid most of human indifference. It can be blamed for the fact that the communities of the two neighbouring countries are not eager to learn about each other. The negative stereotypes – being a source of concern, if not hostility – are still holding. These sentiments have been rooted in the history and contemporary times. Wilhelm Gerloff, the author of a sociologic monograph on cash, entitled “Geld und Gesellschaft”, published in 1952 in Frankfurt-on-Main, wrote: Cash is not merely an economy tool; its essence expresses social forms and ways of coexistence. Schefferski’s coin, designed for Słubfurt, does not function as a means of payment. This is the tool of understanding and thought exchange. Its value cannot be overestimated.

Leszek Kania

Originally published in: Exit - New Art in Poland no. 1(65) Warsaw, Poland 2006

ART´S COGNITIVE PROPOSITIONS

By a remarkable coincidence, in September of last year our art scene witnessed three facts, together marking a path for art’s aspirations. The Neo-Avant-Garde Manifesto was presented as part of the Incredibly Rare Events exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, almost in tandem with the idea of the work of art as a koan, serving as a basis for the exhibition and the theory sessions organized (…) at the MCSW Power Station in Radom, and at the same time, at the Passengers public art festival, a cognitively intriguing object fell into my lap: a coin worth zero units of an undefined currency. Of course, these three facts far from a summer make, yet we should note that, although they use different techniques, they have one thing in common: they focus on the cognitive aspects and capabilities of art.

We could dismiss this and say that everything has already been done in art (and several times over), but I am convinced that it is not in our interest to treat these ideas this way, or trivialize the coincidences behind these events. This is because they appear in a situation which, I believe, is marked by two factors: a lingering ideological impasse and an overload of information. We live under the pressure of a vast amount of endlessly incoming information, which mainly results in the cognitive chokehold of concepts that have already been articulated, with no prospects for new horizons of ideas. These two factors are mainly reproduced in activities which, however well motivated, are now commonplace; we cannot say that these activities are utterly fruitless, but they do not alter the current situation as far as we would like. A hallmark of this situation (and not only in art) is the sense that we insufficiently use the potential of information and ideas that we have at hand and in range of our intellectual capabilities. (…)

Why are cognitive practices so vital at present? It is easiest to draw from the perspective used by cognitive psychology, which explains man’s behavior as delineated by cognitive structures and processes. People can make a substantial changes in their behavior, altering the way they perceive reality and process information. (…)

Reality is too important for us to give up, saying it exhausts us, resigning from attempts to cope with it – this is the basic message behind cognitive practices in art. (…)

If we should seek to put reality in order, we need to find a new cognitive key. But what of the coins we mentioned at the outset? In the Passengers festival, whose theme this year is Money For Nothing, Roland Schefferski created a small amount of coins with a value of zero. He tossed them discreetly on streets where the paths of the rich and the poor intersect. Who would not stoop to pick up a coin? Most of us are aware that we ought not show disrespect for money we chance upon, lest money should take offense and condemn us to poverty. The passer-by thus humbly bends over to pick up the glistening disc, stares at its face, and cannot believe his eyes. What? Just zero? Has money sunk so low in our financial crisis, and is this why it was discarded? Or maybe the one before the zero got rubbed out? But nor is there a name of the currency, only the inscription “Isn’t Everything” followed by a question mark. To hell with it! Zero certainly won’t bring any happiness! The disc is corrugated on the edge like a coin, so this is unlikely to be a game token. Should he toss away this zero or keep it? Maybe it is some kind of advertisement? Better to hold onto it and ask around. But what can be the meaning of money that declares itself to be valueless? Thus begins the communicative virus of stories, questions, and suppositions. Schefferski set in motion the tiny process of circulating non-money, which turns into only a shred of information – but the information is there. He neither has nor wants to have any control over these processes. Nor has he left any sign that this is connected to art. Furthermore, those who are aware that this is part of an art project lose out on a key attraction: the uncertainty and surprise that jog the mind. The value of this “zero” coin depends on what it inspires a person to think; a lack of reflection makes the object worthless. Placing it in an art gallery would reduce it to a clever concept. The place of this non-money is in the head of its finder and the people he or she talks to, this is where the cognitive potential of the zero nominal comes to the fore.

This is the second time that Roland Schefferski has used coins as a medium, injecting a cognitive ferment into the circulation. In 2005, in the border towns of Słubice and Frankfurt (Oder), he “lost” coins with the Polish/German inscription “To dotyczy Ciebie – Das betrifft Dich" (“This concerns you”), a work covered in Obieg magazine, “Miasto jako artystyczny projekt – Słubfurt!” [The City as an Art Project]). He discreetly documented the various ways the finders of the coins behaved, and above all, what they communicated to other passers-by. In a film he made in Warsaw, he captured how a coin traveled between roller-skaters in Castle Square.

In both of these actions, Schefferski’s coins acquire added cognitive potential through the very fact that they are not immediately recognized as art projects. They first present themselves as symptoms of an unsolvable social phenomenon, or, to borrow from Beuys, we might say that, on a microscale (for this is the scale of coins), they carve new paths in social behavior. Schefferski’s work appears without the natural context of art and its aura, which does not mean that it ceases to be art. It is one of those kinds of public art that independently seeks participants, more than viewers.

Theoretical and practical activities that seek to change cognitive structures and processes address the core issues – the relationship of the subject to the reality he/she experiences and helps to shape. Along the way, errors and dead ends will inevitably crop up, but this is a crucial task of civilization: to break through the excess of information and interpretations, to perceive and comprehend what has not existed for us, though it was right before our eyes. This is also a challenge for art. Cognitive proposals also, perhaps, signal a time of manifestos – the need to work together, the need for activity which does not subordinate itself to what others are doing, but offers a synchronization with them.

Grzegorz Borkowski

This excerpt is from the text "Kognitywne propozycje sztuki" originally published in: Obieg - Art Magazine, no 02/11 Warsaw, Poland 2009

A FEW REMARKS ON ANOTHER GERMANY? PROJECT

The central concept of statistical mechanics, and statistics and probability theory in general, is the “expectation value.” In statistics, the expectation value is what we can predict. This is the statistical future, the future of probability equations. We know no such thing in art or in what concerns us today. Physics and art have intersected here many times, in a variety of ways. A psychological approach to expectation value is what Roland Schefferski explores in his latest action, titled Anderes Deutschland? – Another Germany?

From the very beginning of his independent path as an artist, Schefferski’s work has been unlike what we have seen and recognized as art. To understand this, we ought to understand what art is in general. And it turns out that the best approach to art is to see it as a “family of meanings.” This means that the concept cannot be described through a clear definition; a family of meanings is a group of concepts that the classical differentia specifica and genus proximum cannot exhaustively describe. Schefferski’s projects do not focus on producing artifacts, on producing art objects we might use to fill in the “unidentified spaces,” creating a new being, an intentional being, which precedes the aesthetic experience. Roland Schefferski explores relations, in particular memory relations, reconstructing what happens in people’s historical memory when they participate in culture.

To some extent this action pertains to money, but only in a sense. To understand this sense, I would mention The Philosophy of Money, a book (for this is the title of a book) published in 1900 by Georg Simmel. This is a philosophy of money, though Simmel never focuses on coins or banknotes, or percentages, or any of the economic values we associate with money. Simmel finds a deeper level than Marxist historical materialism, i.e. the relationship between production and social class. This deeper level he calls the level of culture and life. It is life that leaves traces behind in the form of culture, and when it reaches a contradiction, says Simmel, between what life has produced, and the fact that it yearns to move on, to develop its élan vital, as Henri Bergson would put it, a crisis occurs; overcoming this crisis is the next step in the development of a culture. In this process, the basic means of cultural communication is money. Approached in this remarkably abstract fashion, money is a social relationship. Von Neumann saw numbers in a similar fashion, stating that the Indians invented numbers, having invented the zero. Von Neumann said that numbers are sets, but they are empty sets. Zero is an empty set, while one is a set composed of two sets – a set whose sole element is zero and an empty set etc. Thus money, conceived as a number in von Neumann, is the basis for a philosophy of money as pure, “empty” possibility. There is no such thing as money.

When Simmel passed away, he became a bedrock of sociology, and a prophet in terms of the philosophy of money. This prophecy came true only when hyperinflation ensued and it turned out that a wagon of money could only get you only a bun. The expectation value collapsed.

I shall return in a moment to the latest work by Schefferski. First, however, I will say a few words about his work so far. He has made remarkably interesting pieces on collective memory, individual memory, and how culture is created, how it pertains to life, to a process that encounters an obstacle in its own product. What he does is art in that it examines memory… Roland Schefferski has examined the relationships between forgetting and remembering, forgetting and repressing nearly whole epochs of historical periods, places, locations, and regions, such as the “Recovered Territories,” the “Western Lands” where contradiction unfolds, populations are swapped, and all memory is repressed. He has examined this memory, reconstructed and collected it, shown the empty places that need filling, such as those “undefined places” in Ingarden or the empty sets in von Neumann, or the meaning of money in Georg Simmel.

Schefferski produces social relations that stand in for money, much as money stands in for social relations. Money does not exist, in fact; it does not exist, much as numbers do not exist, they are empty sets. Simmel mentions this, and he is correct to say that interpersonal communication is far more important, and that the fate of money depends on the individual, and not on social, “economic,” or collective movements, or collective activities. This, I believe, is the topic of Schefferski’s latest actions.

Roland Schefferski slips from the viewer’s field of vision, his partner in a conversation on the future of social relationships. Tossing coins, imitations of money, means of communication and driving culture, he urges reflection on what we want and what we can expect. An open society, or perhaps a fortress in which a nation, a race, “our” religion will survive, or gender as a tradition-honored role?

Piotr Olszówka

This excerpt is a fragment of a presentation for the Another Germany? Project at the UTP Gallery at Humboldt University in Berlin, 2017

INVENTORY

It was Schefferski’s first artistic realization relating to the history of the city of Zielona Góra and to the history and the collection of the Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej (Lubusz Land Museum). He created a monumental installation entitled “Inwentaryzacja – Bestandsaufnahme” (“Inventory”) at the “Nowy Wiek” Gallery in 2003. This was composed of relics with German cultural origins, which were from the collection of the former Heimatmuseum (Local Museum). The exhibition generated a considerable stir and strong emotional reactions, giving rise to an important voice in the discussion on European cultural heritage.

Leszek Kania

This excerpt is from the text "From the Life of Europeans" published in: Recall - catalogue by the Lubusz Land Museum in Zielona Góra, Poland 2014

THEY´VE JUST PULLED OVER

In selected places around the town I wanted to emphasize the phenomenon of otherness. A number of camping vans packed full of clothes were arranged to be moved from location to location. Trough the appearances of these traces, I intended to create a situation in which it would be possible to observe the reaction of the city residents and their ability to accept the foreign newcomers.

My purpose was to create a work that would, among other things, test the memory of the Shoah, while updating it regardless of the outcome. We have a tendency to treat the Holocaust as a closed chapter of history, with no ties to the present. Consequently, we are practically able to file it away ad acta. The anachronous attempts at commemoration of the Holocaust led me to reflect on what would be an adequate form for its contemporary representation.

What should the Holocaust remembrance be? Should it be merely a way of recollecting the past, putting names on something that actually has no name and cannot have one? Passive forms of commemoration do not update memory. If anything, they facilitate our taking of a conformist attitude to reassure our conscience. Our memory can be short-lived and selective, sometimes it can be deceptive. Having come to understand the enormity of the suffering caused by one human being to another, we have let ourselves be persuaded that Shoah has made us sensitive enough. For too short a time, as it turns out.

Memory of the Shoah is possible only in the active sense. What is more important in my belief, in the confrontation with the deceptiveness of human memory, is the never-ending attempt to make people sensitive to people, to their suffering, which can prove to be ours.

Can I sensitize people by representing human absence with the help of material things? By attempting to draw attention to the existence of some unknown newcomers in a symbolic sense I am reversing the process of transforming the subject into an object. I wish to inspire the viewer to imagine the owners of these things. These are not the traces left by people who are no longer here, but traces of people still present among us.

Roland Schefferski