EMPTY IMAGES

A few reflections on the work of Roland Schefferski

Pictures can be veiled, covered, or removed, for instance, as a way of boycotting something we do not want to see, as a show of censorship, a gesture to let “things cool off,” to stifle too much visual stimuli. The removal of pictures can be seen as a sign of loss (something was there, but now it is gone), or as an attempt to tear off layers that obscure “another picture,” much as one strips layers of paint from an old, wooden piece of furniture, or uncovers a fresco on a wall.

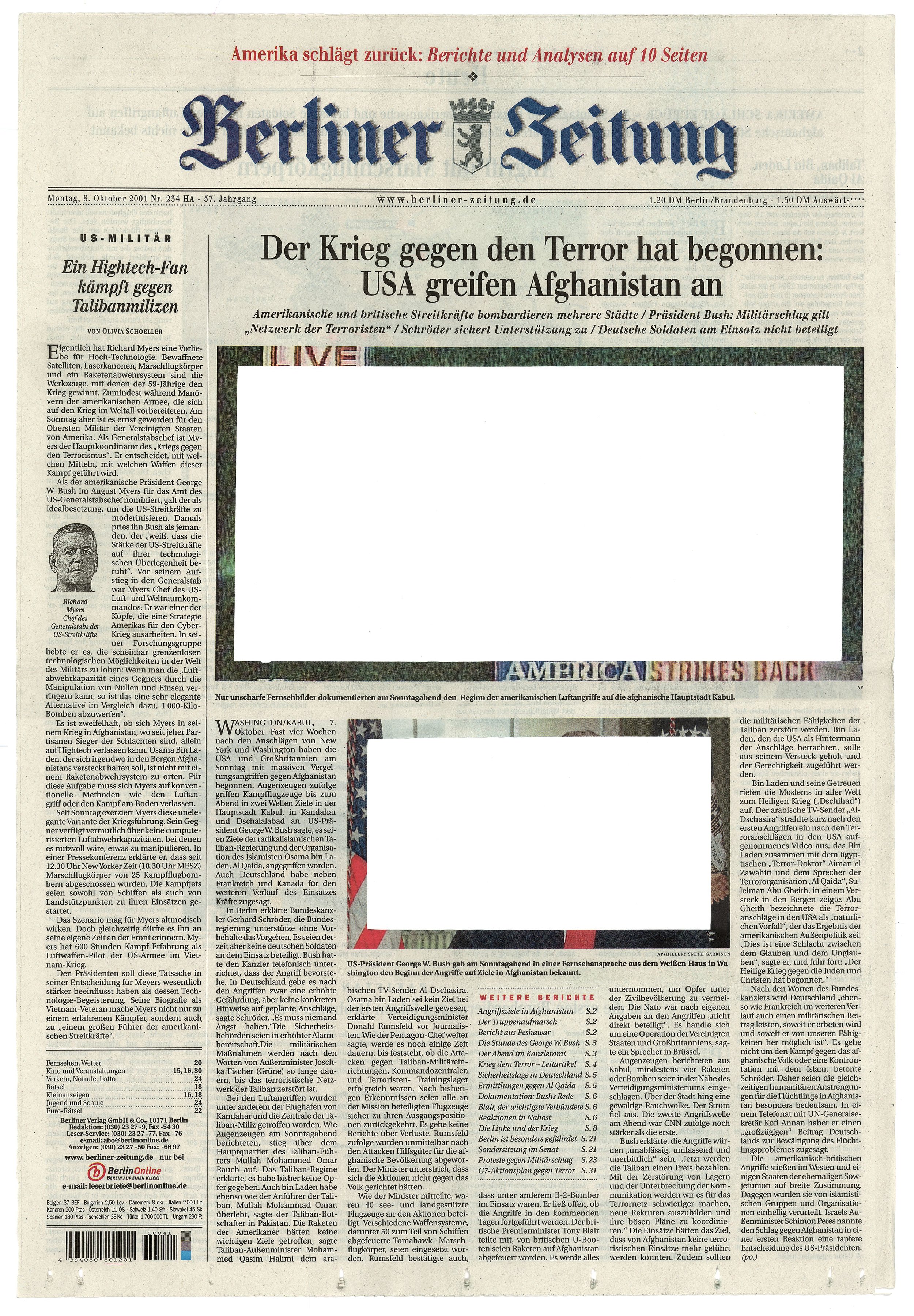

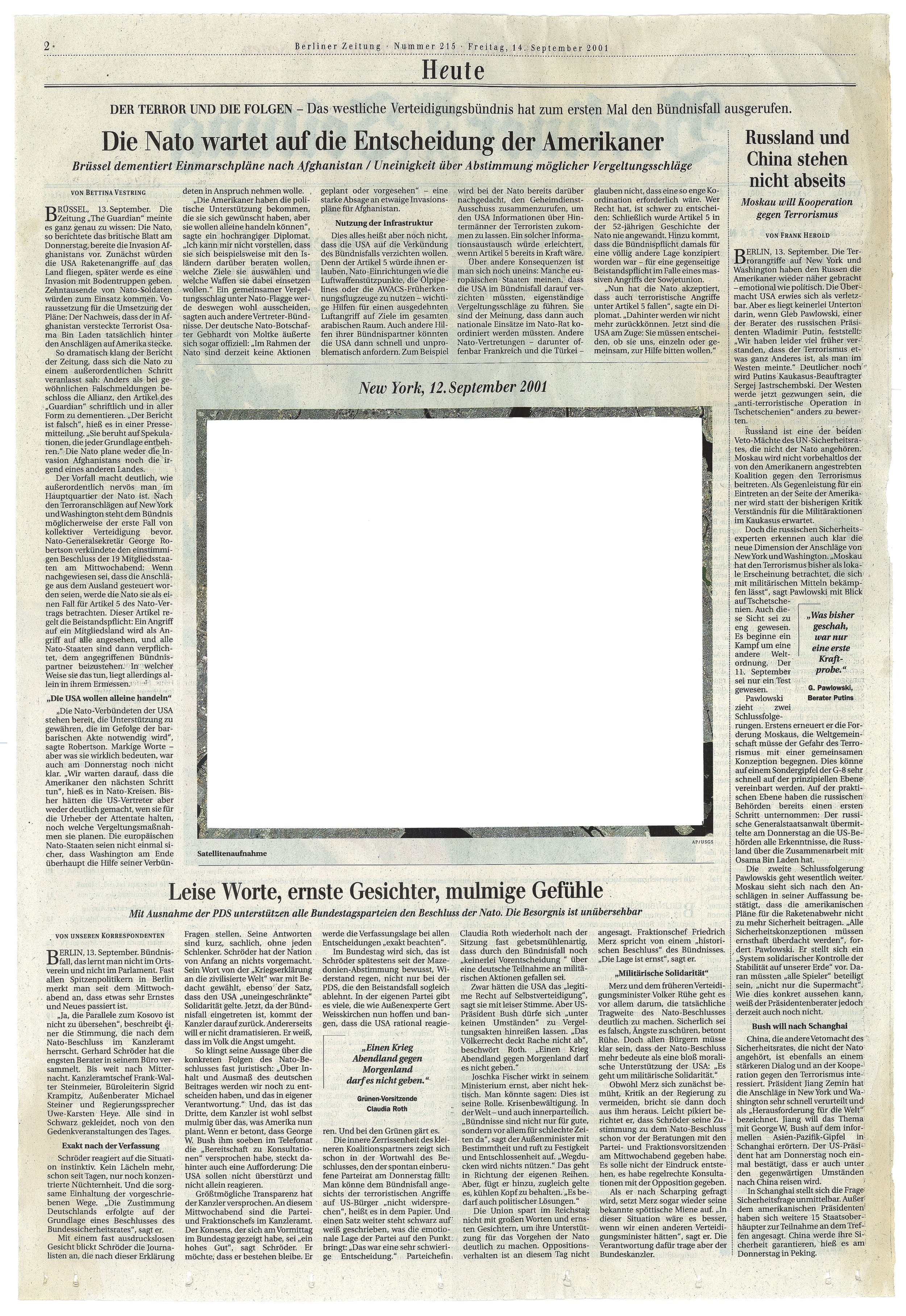

In his series titled "Empty Images", Roland Schefferski removed the photographs from the front pages of The Los Angeles Times and Berliner Zeitung, and this simple gesture evokes a seemingly simple reflection: something here is missing. And so, instead of calmly reading the paper and browsing the photographs, we see the void, the white space, the framed area. The artist left a narrow, color frame where the photograph once was, thus reducing the scraps of images and words to a passe-partout. The empty frames, like silence, can only be indicated, it is the opposite of presence, of a picture or sound. We primarily read the artist’s gesture as an invitation to fill the gap oneself.

In much of his work, Roland Schefferski shows his remarkable ability to subtly enter the sphere of the reality that surrounds us, as if he sought to ascertain if we do not lose some particle of our past and identity in the objects, clothing, images, and identities that flow through our lives. In 1997’s "Pictures Erased from the Memory", he also cut certain motifs from photographs, depictions of the lives of Berliners from the early twentieth century. In this way, he evoked the memory of ordinary people, whose frail remnants are often wiped out in the noise of History. But he also invited viewers to make the effort to replay events, to imagine the past based on fragments of pictures found in storerooms or the private nooks of everyday life. "Make Your Own Picture of Berlin", Schefferski called out to viewers in a work displayed as a billboard in 2000 in Warsaw. The artist sees old photographs, much like the objects, as an important vehicle to the past culture – in his own words, they hold vestiges of our human activities and enclose the information encoded within them. But do the contemporary objects, media images, newspaper photographs, and advertising photographs that flood our surroundings serve as a sensitive record of human fate, can they be a document of our (whose?) presence?

In "Empty Image", the artist’s work might be compared to the Deconstruction method (Derrida), an attempt to tear off the masks and layers applied by the world’s media, which has overpowered how we see, think, remember, and imagine. But the artist’s special deconstruction of reality is merely the beginning, it rouses the viewer to enter a crack that only he has held open. The empty places left by the pictures are a signal to begin uncovering the problem, instead of hiding or smothering it. Perhaps the power and valor of Schefferski’s concept is in this invitation to reflect, in this subtle artistic provocation. But are we not helpless against the artist’s challenge? What information can we draw upon to fill the gaps he has left for us? Are we capable of creating our own vision of reality? Can we draw from our own experience, from individual or collective memory, sensitivity, imagination, learning, common knowledge, or from the global web of information – the Internet? This array of questions shows that the artist has prepared a special space of discourse. This is a disquieting and dangerous space, because it reveals a confusion we presently struggle to name, we have lost the ability to clearly depict our presence and look critically at the images that assail us.

Through contact with virtual worlds, on television or the Internet, we are prone to accept, modify, and mix various aspects of identities, various points of view. This leads to the multiplication of the subject. According to Derrick de Kerckhove (1996), identity now derives from a point of existence, and because we exist in many points at once, we have a multiplied identity – but does this entail the multiplication of the world?

In "Empty Images", does the artist juxtapose the points of view of Berlin, Los Angeles, and elsewhere on the map, or can we glimpse a person in this web of newspaper “gazes”? The figures shown in the glossy magazines and the daily newspapers, in the media, are more signifiers than real people. Both the contemporary photographer and the philosopher reflect on reality by creating their own version of it. In either case, this comes from an interpretation of the world. Press photographs depict not reality, not events, but politics and ideologies, they speak the language of power and advertising, they are often creations of reality or simulacra, as Baudrillard would say, signs which less represent reality than fictions. Yet, as Vilém Flusser writes, reality and fiction cannot be unconditionally distinguished based on the criterion of truth. ‘Truth’ alone is a mere projection of our present knowledge and level of information. However, this knowledge and information are created by the media. Do we have our own world, outside the media and beyond the newspapers?

Roland Schefferski’s newspaper in "Empty Images" is not, therefore, the material of his art, it is no result of the process of “cleansing” pictures, it is not a sphere of aesthetic contemplation, it is a sample taken from reality and subject to delicate interference, in order to show the murky situation between the pictures created by the media and the visual culture, and our capacity to create images, to tell our own, human stories.

Two philosophers have given us essential insights into the significance of pictures in our lives. One is David Hume, who said that we create pictures in our mind; the other is Heidegger, who expressed a thought that now seems natural to us: the world becomes an image. Schefferski, it seems, prompts the viewer to seek the meaning of the picture in him/herself, as opposed to in the “digital imagination” (A. Renaud’s term), and to nurture mistrust toward a reality woven from pictures, particularly given that, in our day, they smooth out life’s ambiguities, removing suffering, old age, or death. Bad news sell badly and puts politicians (and average citizens) in a foul mood.

Today, instead of adding to the pictures, the artist has noted the danger in amassing them and their capacity to manipulate. Back in the 1930s, Walter Benjamin called attention to European culture’s new predicament and the individual’s subjectivity in modern society. He saw changes in the individual experience, owing to the progressive mechanical reproduction of images and the excess of stimuli, which he called “distractions.” Changes in civilization and perception are not accompanied by moral reflection, while the pace of the development of technology and value judgments are inconsistent. Benjamin says that in place of experience we have shock, while Paul Virilio conceives contemporary culture as exchanging “events” (Heidegger) for “accidents.” Of course, as cultural scholars believe, an excess of powerful stimuli causes a sort of cleansing and a readiness to receive new input, changing not only the content, but also the nature of our perception and the image/reality relationship.

Photography turns gestures and movements into static forms, reduces complex events into moments frozen in time, breaks the world’s continuity into parts, fragments, select frames. We generally trust photography, we have an instinctive need to seek relationships between the image and a certain segment of reality. Yet is what we see on paper the same as what we can touch or see in front of us?

Following Paul Virilio’s train of thought, we note the transformations that have occurred in the development of computer technology, and thus in the sphere of relationships between the image and presence, or the trace of presence. While in the previous epoch (of the dialectic of the image, i.e. the epoch when photography, cinema, the photogram were being developed), we could speak of the presence of the (photographed) object, of the presence of the past, “captured” on a photographic plate (a presence which Schefferski often evokes in his work), today, in the epoch of “the paradoxical logic of the image” (Virilio’s term), of the televised or digital image, we have the annulment of the object’s image in real time, as virtuality has come to dominate the current event. Advertising and news photography no longer secures a memory or trace of the more or less distant past, it shows the desire to suggest the future. Contemporary media images overwhelm and invalidate the past, the real presence in a specific place, they create the future, seeking to overtake real time. It is now less historical changes and fortunes that make up our lives and existences than the dynamics of perception, the constant necessity to come to grips with the world, forever distracted in the stream of visual impressions. The world seems to flash and fade, it eludes us, the prevailing aesthetic is speed and disappearance, as Virilio states. Are we therefore creating a civilization that keeps us from anchoring ourselves in the present and in history? Instead of assisting communication, information exhausts itself in staging communication. Instead of producing meaning, it exhausts itself in staging meaning (Baudrillard).

Contemporary pictures not only alter our sense of time and our rootedness in time, they also reimagine space. The public space is jam packed with images. Virilio even says that the public image has consumed the public space.

Many insightful examiners of contemporary culture have called attention to the world’s carnivalization, theatralization, Disneylandification, and mediatization process. We are, in effect, dealing with the aestheticization of the upper spheres of life (Wolfgang Welch): bodies, homes, streets, cities, politics, tourism, even wars, which ultimately bolsters the zone of artificiality, the total consumption of images, a desensitization, a callousness, a deadening of the sphere of emotions, a shift in identity (Baudrillard, Welch, Ferestone, Jameson, Bauman), and thus a strange and unsettling enchantment of ourselves and the space we inhabit.

From the town, as theatre of human activity with its church square and market place bustling with so many present actors and spectators, to CINECITTÀ and then TELECITTÀ, bustling with absent televiewers, it was just a short step through that venerable urban invention, the shopwindow. This putting behind glass of objects and people has led (...) to an optoelectronics of the means of television broadcasting. These are now capable of creating not only window-apartments and houses, but window-towns window-nations, (…) that have the paradoxical power of bringing individuals together long-distance, around standardised opinions and behaviour. (Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine, 1994). We have lost the ability (assuming we ever possessed it) to discriminate between the world and the image, as if we lived in an image, as if we lived and breathed images.

There was a time when people yearned for and worshiped pictures, and their production process was assigned strictly to the talented and indoctrinated. There was a time when their creation was forbidden and a time when their execution followed careful rules. There was a time when they were stored most vigilantly and a moment when barbarians entered and destroyed them. Baudrillard aptly describes the historical process of the triumph and fall of pictures in culture, through the development of their technological reproduction, while noting that our epoch has lost its sense of reality, creating simulacra, imitations, fictions in place of reality. Signs and pictures drift, detached from their meanings, and this affects how we see. In our day, we investigate how photography and media images – which we create ourselves – construct our world, how they give it meaning, and what meaning this is. How the medium affects visual culture and our perception of reality. Pictures have long ceased to be innocent.

The artist’s distrust toward images might seem peculiar – according to popular wisdom, it is artists who create pictures. Schefferski, meanwhile, does the opposite. Cutting the pictures from "Empty Images" is a gesture that disassembles the “vision machine.” The artist puts us to the test, asking us if we can still see anything, if we can still imagine the world in our own pictures?

Roland Schefferski calls his piece "Empty Images". In another of his projects, where he cut motifs from old photographs of Berlin and Gdańsk and, speaking up for the truth of the people and cities pushed into the shadows, for our ability to imagine the past, he used both the Polish and German languages. The photographs from the early twentieth century could “commemorate” an individual world (Gdańsk, Berlin), note a real presence, while "Empty Images" pertains to the global village, to the McWorld, to a sphere where no one is capable of telling individual human stories tied to a concrete place.

"Pictures Erased from the Memory", "Ausgeloeschte Bilder", "Empty Images". In these projects the artist uses a variety of languages, furnishing the word “picture” with a variety of adjectives. As a European residing in Berlin for many years, he could select a single language in his work, such as English or German, or, as a Pole, stick to the Polish language. The word, its sound, even its graphic inscription, helps create the emotional, historical, cultural context etc., and to this Schefferski is particularly sensitive. This is why the artist changes his language when he shifts his attention to a new place, to a new human story. He tries to open the linguistic space in which we should seek the meaning of his work. Speaking involves breathing, it is a right, a duty, a game. The very intonation and substance of language create chunks of knowledge, Roland Schefferski wrote in a statement accompanying one of his projects for Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw. He sees language as more than a means of communication. Language and the word absorb history, its sounds evokes emotion, mobilizes memory, helps create our identity.

In "Empty Images", Schefferski shows us various newspapers: the German Berliner Zeitung, and the American Los Angeles Times. The English (American?) title of the project alludes to a particular linguistic zone. The English word empty has a wide range of meanings, from hollow, to vain, pointless, or unreliable. The use of a certain language can also point to a geographical, political, and cultural context, indicating a specific realm of thought (American, in this case), which is so important in the global circulation of information.

In his subtle, trademark fashion, Schefferski juxtaposes objects, symbols, images, and words. It seems all this is familiar, the artist has not really added anything, at most he has shifted the focus, changed the context, removed certain parts or gently placed his gesture in the real reality. Through this juxtaposition he creates a new “text,” which invites us to a new “reading” of a world we believe is familiar and assimilated. Making subtle interventions into the realm of objects and pictures, the artist keeps them from freezing in self-contentment, he will not let us forget about the possibility of a “different” gaze. His installations and interventions always prompt a sense of: What do you think about that?, and This concerns you. In this way, Schefferski combats the distractedness to which media has accustomed us, he wants to prevent the entropy of the imagination and keeps inviting viewers back to a careful and critical reading of the world. Perhaps this is the role of the artist in our day?

Mirosława Moszkowicz

Originally published in: Collection of Contemporary Art - catalogue by Collegium Polonicum in Słubice, Poland 2013

BEHIND IMAGES

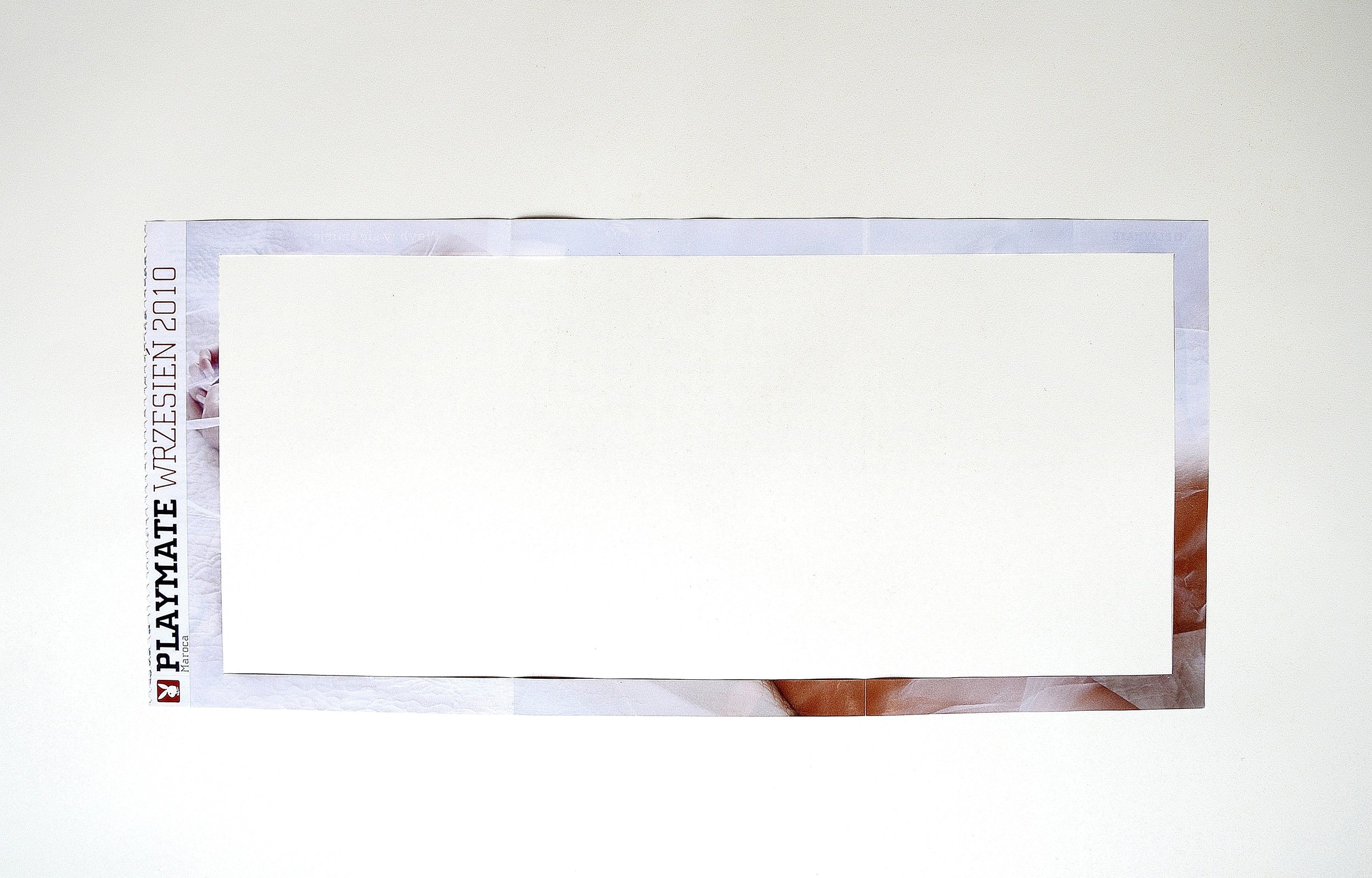

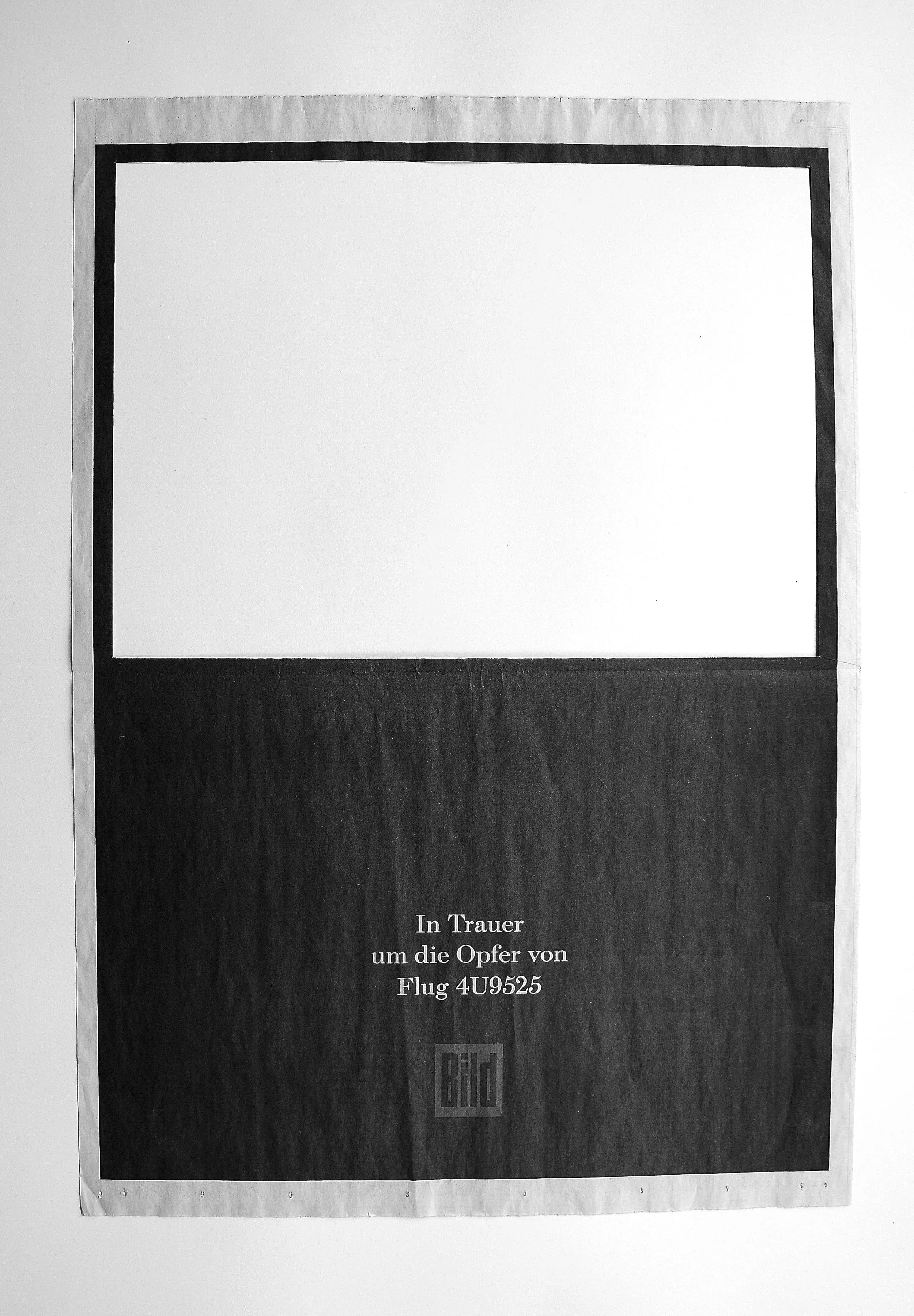

Since the 1990s, Schefferski has focussed on the function and the effect of visual media. One of his artistic strategies is "extinguished" or "empty" motifs of initially historical photographs, a focus since 2000, printed images in newspaper pages, which he cuts out so that only a narrow peripheral edge is left. He is concerned with highlighting the manipulative character of visual media and to ask the viewer questions about the story behind the missing image. Most recently, he cut-out the screen windows freeing deeper layers of newspaper, these editions confront images from the rear with the front page text. Schefferski has achieved the effect that the viewer has been dealing with this information behind the image and the manipulative character of media encryption.

Schefferski has become known on the subject of cultural and collective memory in Germany and Poland with objects, installation and conceptual art. In recent exhibitions he showed larger series of cut or missing images to illustrate the problems, lost by war and persecution through previous image media. In the exhibition "Behind Images" however, he focuses on the effect of the single object. The excised Death announcements for "flight 4U9529" he matches with an almost identical page of the New York Times of 5 May 2015 in which the corresponding white text advertises on a black background for an "International Luxury Conference" and next to the obituary of the image more obscene acts. In a two-game dual series, the newspaper Die Welt from 5.10.2012 and 10.28.2013 he cuts out from the front pages of reproductions of the renowned painter Gerhard Richter and Neo Rauch, exposing examples of incessantly recurrent car advertisement. Behind the cut-out window of a promotional bag, the newspaper Welt Kompakt headline is left, therein we question who competes with the text of the plastic bag. The plastic bag of Playboy, however, reveals a cut rectangular form, only just exposing her silvery, inner workings. Anyone who would have expected more is just disappointed due to the subject being Polish issue of the magazine Playboy of September 2010. In a newspaper page with the headline "Polski Berlin - 120,000 Poles live in our city," the artist removes not only the portrait photos, but also the nearby shown Go-Go Dancer and the photos of the "collapsed rush hour". In the case of men's magazines, he debunks not only the well-known role of visual media but criticises the sensationalism of the beholder.

Schefferski dissects images to disclose the meaning behind. He confronts different levels of sharp reality cuts with each other, questions and treats their perception ironically.

Axel Feuss

This text is an excerpt from the text “Behind Images” originally published in: UP Gallery - catalogue by The Foundation of the UAP Poznań, Poland 2015